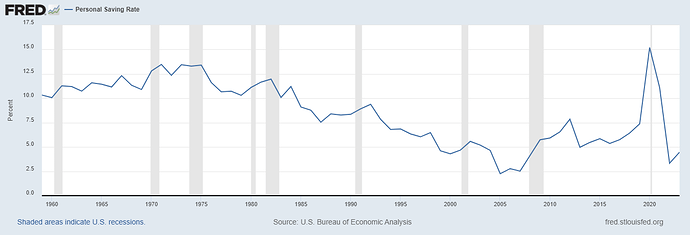

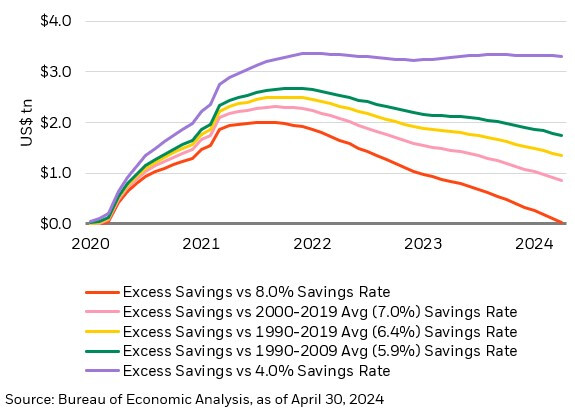

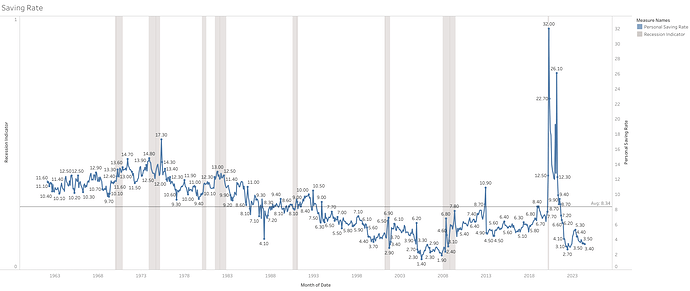

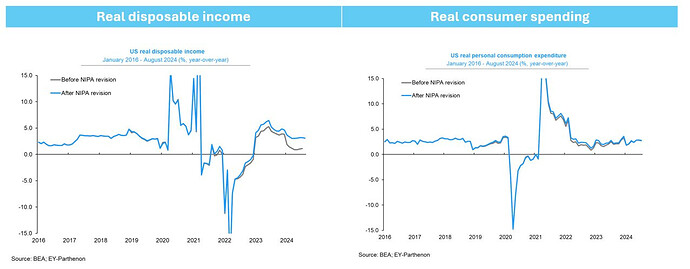

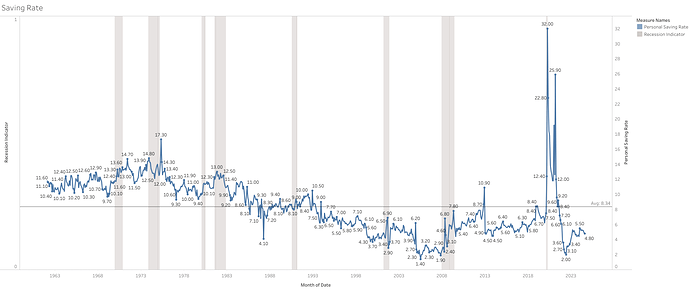

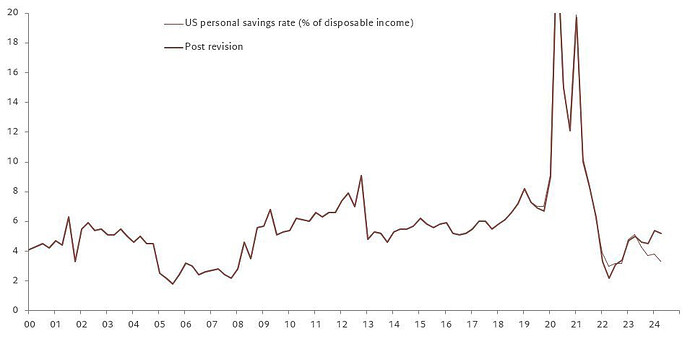

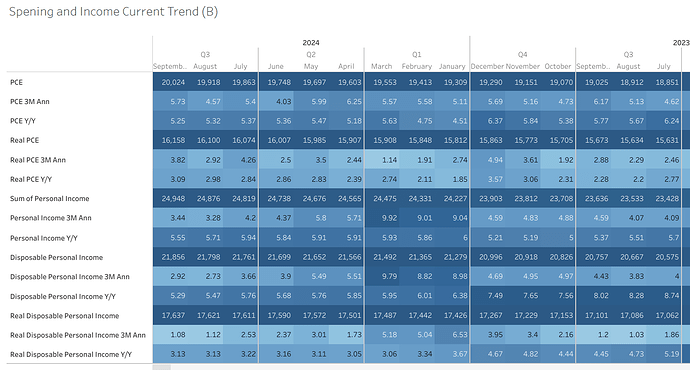

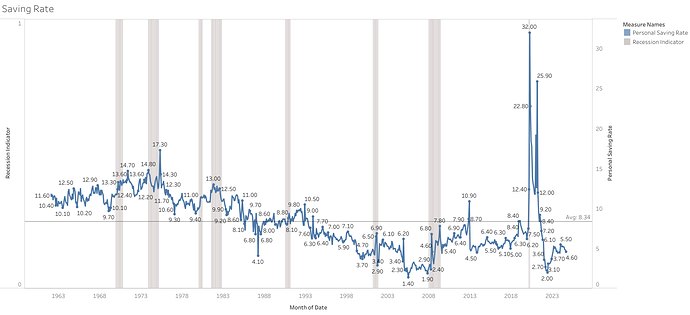

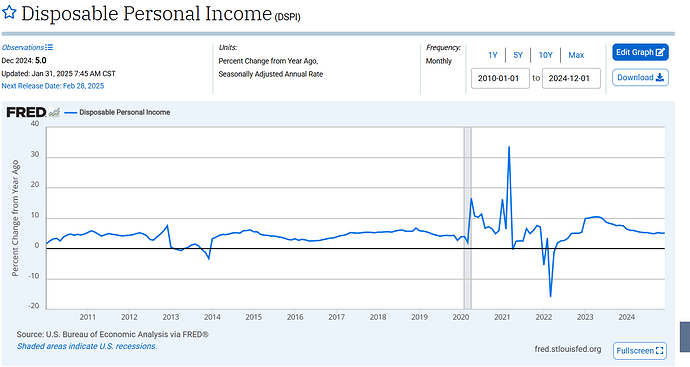

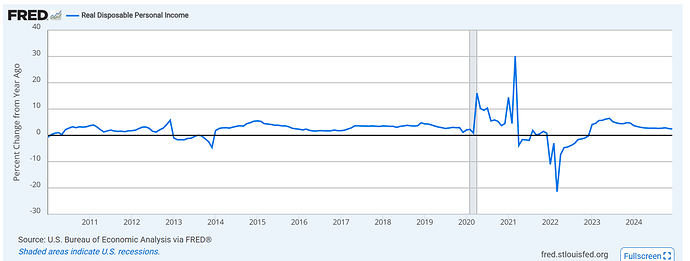

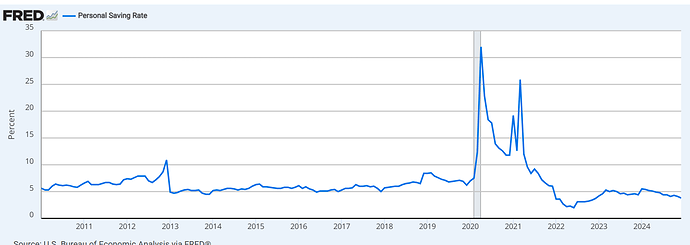

I dont think you cant simply say a trendline is too optimistic and that’s it. Since 1960 the avg and median saving rate is ~8% of disposable income, so pre pandemic savings were on par, actually a bit lower than that (avg 2010-2019: ~6.1%, avg 2016-2019: ~6.2% ).

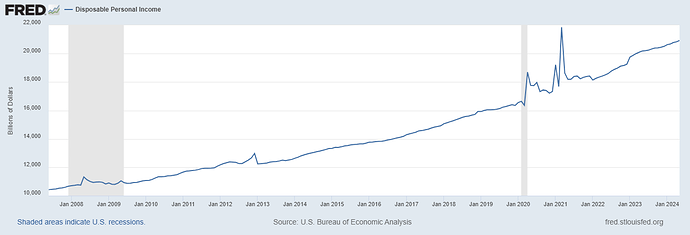

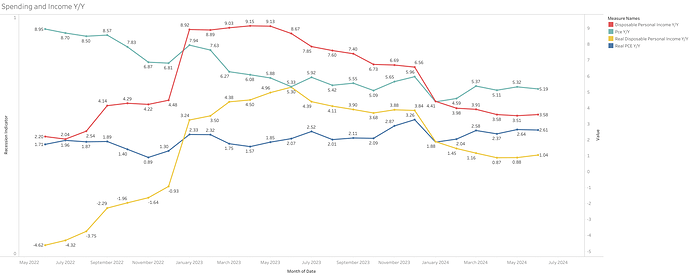

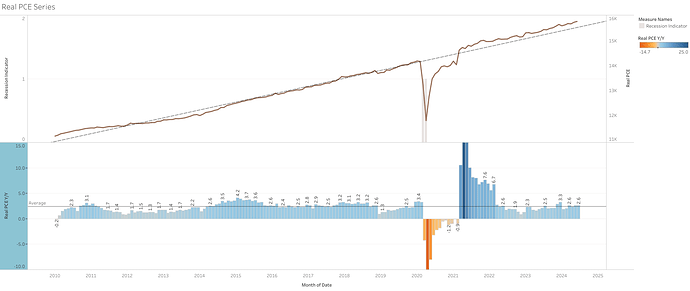

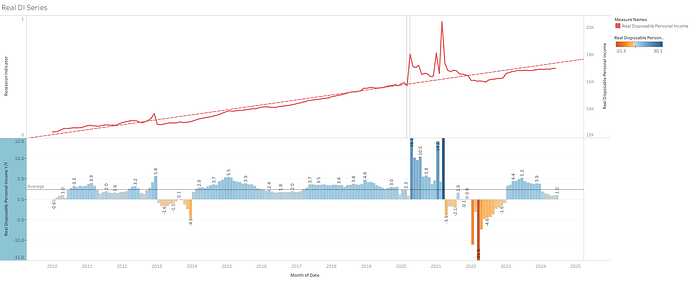

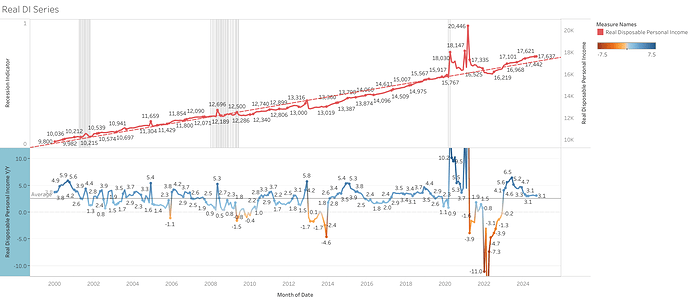

The increase in nominal personal savings since 2016 is mostly due to disposable income growth during this period, not necessarily saving rate increases.

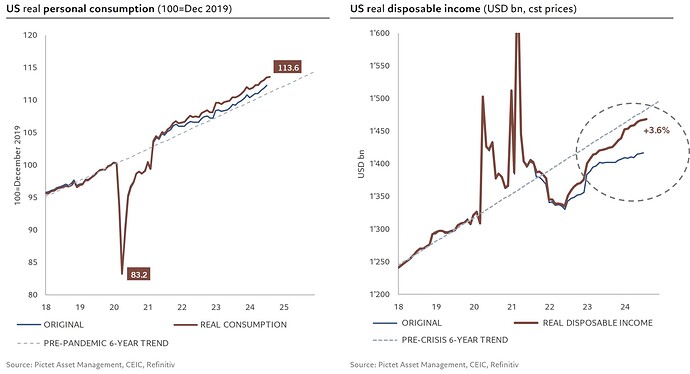

If you think there has been a structural change in consumer saving/spending behaviors that led to a lower than 6% saving rate permanently or a change in consumer income growth trend (which has not been the case until now) that led to a lower savings cycle now, you need to outline your compelling reasons why that is.

I think in this regard if we enter a structurally higher rate environment, savings could be lower due to more money going to interest, but I also don’t think the very low current saving rate will be the new normal either. It could probably be somewhere in the middle, or closer to 6% even.

But we also don’t know if people instead of savings will adjust spending over time, and the saving rate will go back up to the mean again, or if growth in disposable income will compensate for that.

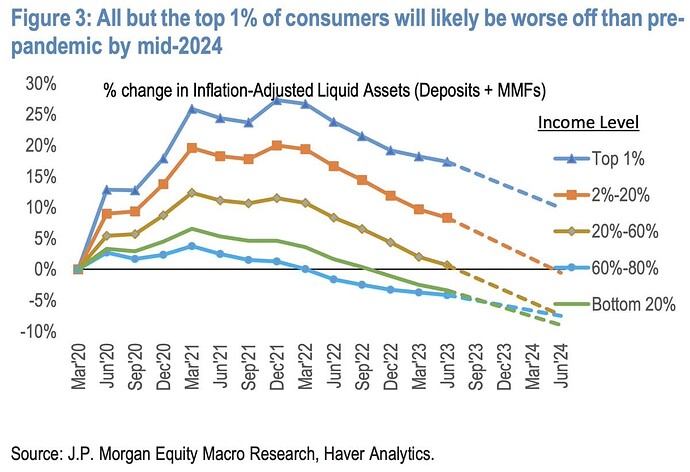

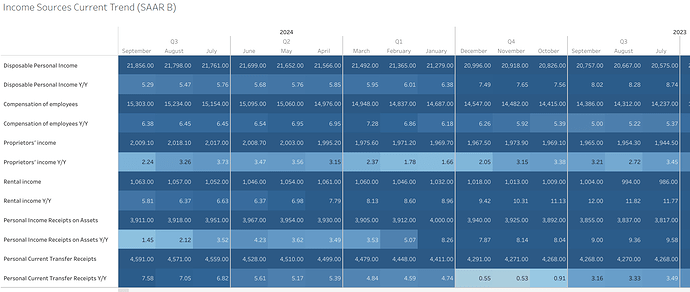

But yes, some excess savings could still be there on other scenarios, but I would not expect to be that much either as I would not do any extreme change, and I would argue for now if it is the case, they are probably mostly now in the hands of the more wealthy, who don’t have the propensity to spend them.

So yes, agree, that savings and income in lower percentiles could be more important, however, data by cohort is not the best, but I will try to see what I can find.

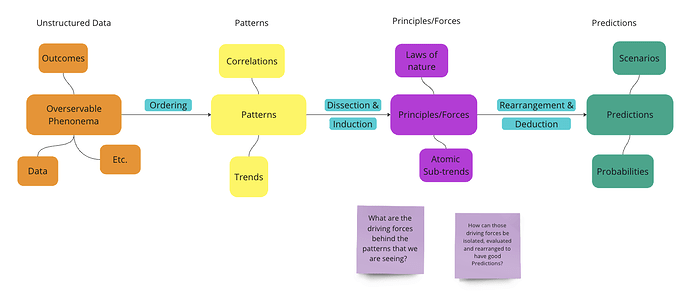

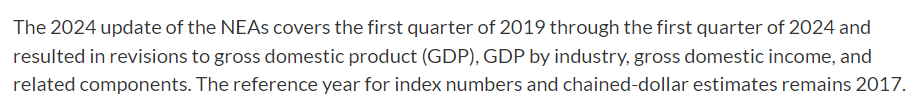

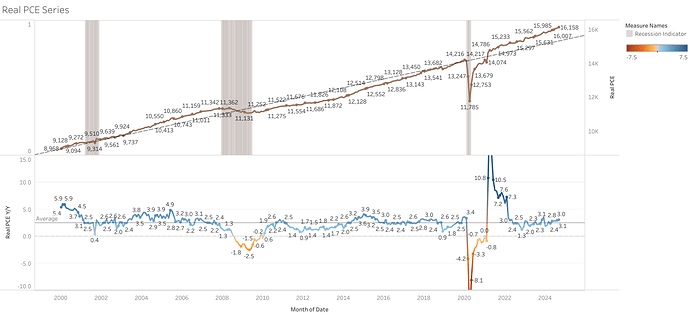

If people misleadingly use the chart on other sites, that’s another problem. The researchers were clear in their methodology and acknowledged the fact in the post that the analysis would change if a different trend was used.

So, what I would say is they probably should have done/publish different scenarios, as with everything is always best.

Yes, sorry, I don’t know where 32T came out, is only 18T in liquid assets.